Everybody Else is a Moron, and Other Reasons to Start a Company

PEOPLE ALWAYS SAY THEY WANT TO START A COMPANY. Nobody ever spends years wishing they could run a company, or track key performance indicators over several quarters for a company. I don’t think I’ve ever even heard someone say that their dream is to lead a company. People are focused with the starting part, myself included.

There must be some sort of God complex machismo Mother Earth cult leader instinct that elevates the filing of paperwork with the State of Delaware to dream-come-true status.

I know from experience that one can over-focus on the starting part. I distinctly remember sitting across from Kevin in the earliest days of Context Optional, both trying to figure out what Step 2 was supposed to be. It took a while, but we figured it out. We figured out what we wanted to build, who we wanted to hire, what motivated us, and what outcome we wanted. But over the years, I’ve come back to that moment when I realized that I had started a company because I desperately wanted to, but suddenly couldn’t remember why I wanted to, or what I wanted to do with it.

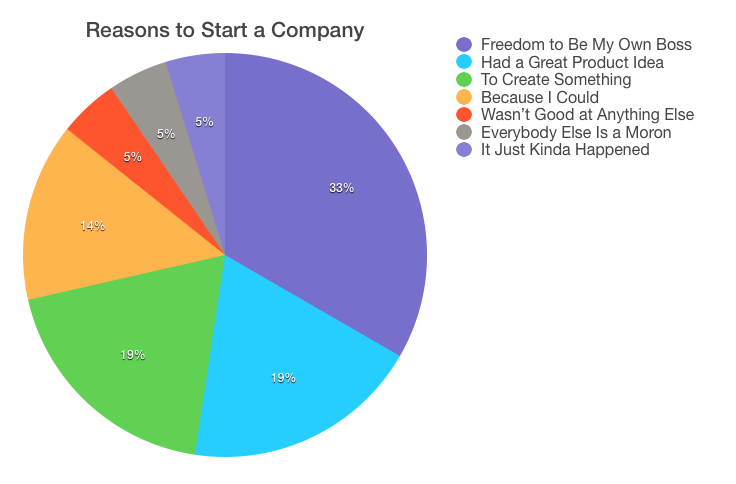

Curious about what caused people to make the irrational decision of taking on financial/medical/emotional/marital risk, I posed this question to 53 founders that I know. A handful replied. Some responses came from founders of companies that have been fabulously successful. Some came from those who gave it their best but didn’t make it. Some are still figuring out which extreme they’ll end up at.

The responses varied. Many founders gave multiple reasons that were completely inconsistent with each other. Some were modest — “I went to academics when I realized I probably wouldn’t be a very good employee. I started a company when I realized I probably wouldn’t be a very good academic.” Others implied it was destiny — “… a chance to change the world.”

FAME AND FORTUNE

Nobody listed the chance to achieve great wealth and notoriety as a reason to start a company. Maybe they were too embarrassed to admit that when they signed their incorporation paperwork, they had dollar signs in their eyes. Or maybe it’s that the people who do it for the money rarely make it far enough to actually start the company.

I’ll admit it, though. Money was at least one of many factors for me. I graduated college with a plan — I’d work at a really fun startup as an early employee, make a bunch of money, then live off that money while I just build cool stuff that I find interesting. One of those cool apps will turn into my own company. So I joined startups that I thought would give me a favorable exit, but none of them did. And I found that I was less passionate about each subsequent one and just chasing the elusive “exit.” So I started a company, in small part, because I thought it was the best chance I had to get to the point where I could have enough money to “build cool stuff.”

The money thing was really a means to an end for me. It wasn’t to be rich; it was just to have some flexibility. And I wouldn’t say it was a particularly good part of my plan. As Cameron Ring, Founder of Plaxo and Dandelion Chocolate, put it:

If you just want to make money, going into Finance is a more direct and safer path. If you want to create something amazing… you can’t beat startups.

That rings (no pun intended) true to me. The potential financial outcome makes starting a company a career option. The creative aspect makes it a passion.

TO CREATE SOMETHING

As I attempted to categorize the responses, I found myself latching onto one particular group. Several of the Founders described the desire to build some sort of entity as their motivation. I’d put myself in this group. When we think about starting a company, we don’t immediately think about products, deals, flexibility, or IPOs. We think about a culture developing as the first employees join, about the inside jokes we’ll put on t-shirts, and about standing up in front of the company to share news, good and bad. Maybe we start companies as a way to start a family without the messy implications of human reproduction.

Most of the people who focused on creation also focused on the team. Joe Chang, Founder of Marin Software, says:

I wanted to have a hand in the coding of something new from the ground up, but also wanted to help build teams and processes that then could stand the test of time.

I Love The Process

Founders who want to build something tend to want to build something lasting. None of the people I polled were into “quick flips,” though I suspect that such a person wouldn’t bother replying (since they’re busy trying to flip something) and likely wouldn’t be a close contact of mine in the first place. But I do feel like there is a Founder archetype who really just likes the process. They like the fast moving nature of it.

They are the fast talking, hype spouting, deal making, adrenaline rushing Founders that I can’t relate to in any way.

Because I Can

We live in a place and time where starting a company has never been easier. Which is not to say that it’s easy, just that it’s never been easier. At the same time, success is no more guaranteed than in the past. Several Founders saw that as a reason to “take the leap” as they say. Either as a personal challenge like Marketcetera Founder Toli Kuznets:

I wanted to see if i could do it, wanted to solve (what i believed) a real-world problem, wanted to call my own shots.

… or just to add variety to a career, like ChoiceVendor Founder Rama Ranganath:

I had the opportunity to do it and it seemed like it would be a unique learning experience.

I don’t think it was the ease of starting that motivated this group, but I think perhaps they viewed it as more of a “why not?” When funding is available, you have the talent to do it, and you have a window of flexibility in your life, why not?

The Freedom of Being My Own Boss

Being your own boss sucks. It’s hard to know if you’re doing a good job, or even if you’re working on the right problems. As a task list motivated person, I’ve always thrived when I’ve been given specific tasks and deadlines. As a Founder, I had to make that list myself and try to avoid the pitfall of giving myself too much leeway or changing the tasks when something more interesting came along.

Yet many Founders thrive on the undirected nature of starting a company. It was the most popular response. Serial Founders like Mike Greenfield, Yael Pasternak, and Waynn Lue cited flexibility as a reason.

I see this as more of a lifestyle consideration. Perhaps these are the people who tend to feel antsy at a 9 to 5 job. They don’t want to be working on the same thing or even at the same desk every day. One Founder told me how, from the beginning, the focus was on integrating the work into a flexible life with school dropoffs and family time.

Everybody Else Is a Moron

By far, my favorite (anonymous) response was:

I thought the guy who started the company I worked for was an asshole and was doing everything wrong. I figured I could do it better.

I’ll admit to looking at Founders I’ve worked for in the past and thinking, “This doesn’t look that hard. Moreover, I’m pretty sure I know what this guy is doing wrong.”

At every company I’ve worked for as a non-founder, there’s been a general consensus among smart ass employees about what leadership is doing wrong and how it would be easily fixed. It’s so obvious.

Trust me, though. As a Founder, it’s less obvious. You realize that those simple fixes you came up with before (“They should just sell the company!” “They need to get rid of half the team and make a consumer product.” “They should just do a talent acquisition and get us jobs at Facebook.”) are not so simple.

Thinking that maybe it’s just a surplus of information that makes it hard to see this obvious fix, I once started asking my team in one-on-ones what they thought. “Come on, Dave. I know everyone must be talking about what we’re doing wrong. What are we doing wrong? What should we be doing?” Nobody was willing to tell me. Could be that we were doing everything right.

Anyway, even if it’s not as easy as it seems from the sidelines, the truth is that everyone is a moron. Some are just better at hiding it. But nobody honestly knows what’s going to happen. Every startup makes enormous mistakes. They churn through execs, they completely change product direction, they target the wrong market segment, they place their bets on an API that gets shut down. The good leaders are the ones who can correct the idiotic mistakes they make on a daily basis. The okay ones can at least spin them in a positive way. The terrible ones claim they don’t make any.

The important thing isn’t to avoid Founders who are morons, it’s to decide which moron you want to work with.

Author’s note: None of the Founders involved in this study are morons. But they’re the exception.

Up next: Founders talk about doing things the “wrong way” and whether that was a benefit or a liability.